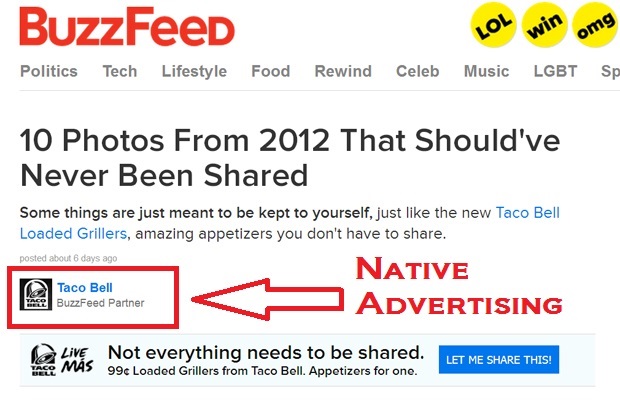

Online readers are seven times more likely to identify articles as paid-for content when labelled “advertising” or “sponsored content” than when badged “brand voice” or “presented by” according to new research.

The research, from the University of Georgia, underlines how confusing the language around native advertising is to consumers – and how the conventional “top of the page” approach to disclosure placement may be wrong.

Furthermore eye-tracking software showed that the position of any disclaimer was also key, with only 40% of readers clocking a disclosure at the top of the page – whilst 90% picked it up ‘in an outlined box’ in the middle of the story and 60 per cent at the bottom.

Bartosz Wojdynski and Nathaniel Evans of the university’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication ran two tests with a panel of 242 consumers.

The pairworked with sample native ads of 500 to 600 words, the first test looked at disclosure language, the second at placement.

In its response to the latest FTC guidance on native ads in December, the Interactive Adverting Bureau (IAB) warned that rules needed to be “technically feasible, creatively relevant, and not stifle innovation.”

Dr Wojdynski said some news organisations – for example the LA Times and Chicago Tribune – were doing a better job than others in using language that made the paid nature of native advertising clear to readers.

As for prominence and positioning, he added: “I’m not sure there is any major publisher that deserves an A grade or first-class mark in this area.

“If the goal is to minimise the likelihood that a consumer will miss the label, publishers need to do a better job of putting these labels in places where readers’ eyes will go. That means not at the top of the page with the banner and navigation, and not in the right rail, where consumers are used to seeing display ads.”

Dr Evans added that the combination of what a disclosure label said, where it was positioned on the page and when it was read had a strong bearing on reader sentiment towards the content and the advertiser.

“For example, disclosing the content as advertising after the consumer has already digested it may help them identify the content as advertising but might not be all that effective in mitigating negative sentiment toward the content or advertiser because they may feel deceived,” he said.

“In that regard, finding the appropriate time/location/language to help the consumer see and understand that it is advertising may afford them the opportunity to process the content with the knowledge that it is an ad. We believe that advertisers would benefit from being transparent in this vein, and furthermore, such an approach could end up being good for business in the long run.”

Read the full report here